Temporary Dental Veneers before Permanent Porcelain Veneers?

Why are they necessary?

Let’s start by making a long story short:

What are temporary dental veneers?

A Selection of Design Factors

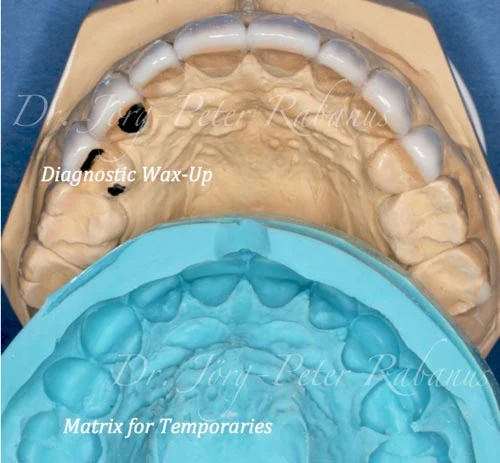

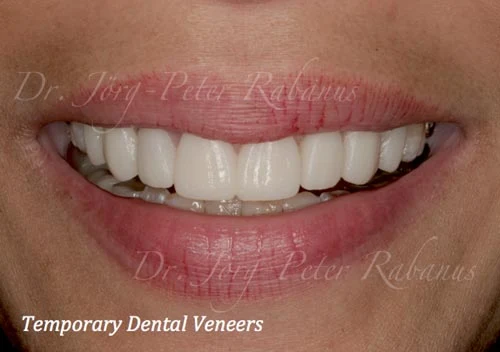

Temporary dental veneers are intraoral duplicates of smiles that were developed with wax on dental stone models. These smile mock-ups on dental stone models are called “diagnostic wax-ups.”

A diagnostic wax-up and its mold that serves as

a matrix to fabricate intraoral temporary veneers

Diagnostic wax-ups are functionally designed. Tooth contour and relative proportions of neighboring teeth are aesthetically optimized relative to absolute funtional harmony considering the dynamics of the mandibular joints and the natural engagement of upper and lower teeth. They are characterized by specific line angles, embrasures, and axial alignments. They include the patients’ specific goals and desires as much as possible within the natural functional framework of their jaws.

Temporary dental restorations are important for

- Testing the patient’s comfort of a new smile design

- Maintaining the tooth positions of the prepared teeth

- Maintaining gingival health

- Maintaining the home position of the mandible and its optimum distance from the maxilla.

- Evaluating all aesthetic components of the new smile:

- Relationship of Smile Line/”Arc” to Lip Line and Lip Rise

- Dental proportions and how they harmonize with the patient’s face

- Individual tooth shapes (such as line angles), contours (soft or aggressive), incisal embrasures, shades (relative to existing teeth, and buccal corridors.

Considering the complexity and benefits of temporary dental veneers, a top cosmetic dentist should help the dental laboratory to design them and place them personally (not assign a dental assistant). Temporary veneers are the most important step of a smile design. They include and represent all functional and aesthetic elements that are developed during a meticulous process of evaluating and defining a dental condition as it relates to aesthetics. In the literature, its foundation has been described as “biomimetics.”

Biomimetics studies structure and function of biological systems. It is the foundation for the design and engineering of dental materials. The cosmetic dentist always strives to rebuild the original biomechanical, structural, and aesthetic integrity of the tooth.

When worn teeth are restored to their original form with porcelain as a substitute, they often recover the optical and biomechanical properties of natural structure.

In the past, teeth were reduced by cookie-cutter like methods using “depth-cutting” burs for an even reduction of the tooth surface as a receptacle for porcelain veneers. Obviously, this does not make any sense, since it would ignore the future outline of the new porcelain veneers. Tooth reduction ended up being too excessive, with unnecessary loss of sound and healthy tooth structure.

However, the most frequent motivation to get porcelain veneers are small and/or worn teeth that need to be restored to their original size or made even longer and bigger, as frequently desired by a patient. In any of these scenarios, the need for tooth reduction is less.

Modern cosmetic dentistry prepares teeth for porcelain veneers differently now. The set ups are more comprehensive:

First, the mandibula’s home position is established and functional patterns are recorded and analyzed. Then wax is added to the models of the natural teeth to rebuild their volume and lenghten their incisal edges. Several mpressions are taken from this so-called “wax-up.”

A variety of PVS matrices are fabricated that aid the cosmetic dentist in relating the diagnostic wax-up to minimal tooth reduction.

Modern materials for the fabrication of temporaries are chemically-cured composite resins, such as Luxatemp, Integrity, and ProTemp. They shrink only minimally when setting (as opposed to older temporary acrylics), they develop minimal heat when setting and are wear resistant and maintain their original color pretty well.

So, how are temporary veneers made?

It starts with a thorough conversation with the patient. What are the current concerns? What are the goals? What is the dental history?

Once the goals have been established, the cosmetic dentist evaluates the current condition of the patient’s mouth and how it relates to the individual smile. Objective references are used to describe the entire scene.

The most important reference is the natural home position of the patient’s mandibar joint in the maxilla’s socket. If the patient received a lot of prior dentistry and/or orthodontic treatment, the chance is great that upper and lower teeth have their maximum contact at a deviated jaw position. This would be a problem, since an adjusted jaw position to changed chewing contacts and shifted teeth is unstable.

“Dental wear cannot be fixed by just placing porcelain veneers if a stable jaw position is not established.”

A smile design with porcelain veneers is really comprehensive dentistry. Many patients have signs of advanced dental wear, which is exactly what makes them unhappy with their smiles. Dental wear cannot be fixed by just placing porcelain veneers on prematurely-aged teeth, if a stable jaw position cannot be established. In fact, an unstable jaw position may be the reason for the dental wear due to the continuous attempt by the mandible to find the position that serves best functional needs.

Hence, a cosmetic dentist verifies and corrects an unstable jaw position first. Now the dental models can be related to each other on laboratory joints. A functionally sound smile design can be developed on the model teeth at a stable position of the temporomandibular joint. The risk for a future breakage of porcelain veneers by grinding habits is diminished (nightguards might still be necessary after completion of the smile design with porcelain veneers).

We now have a “textbook” smile design on dental models. But how does it look in the patient’s mouth? How will the patient like it? We will have to transfer the textbook smile design into the patient’s mouth. This is done by taking impressions of the textbook design in wax. Once the preparation of the teeth is completed, a duplicate of the textbook smile can be placed intraorally.

Since the patient is still numb, he or she will go home and observe the appearance of the new (temporary) smile once the numbness is gone. A shade guide will be supplied which the patient will hold against the temporary veneers at various light conditions to develop an idea about what shade is most desirable.

The patient returns after four days for a conversation with the cosmetic dentist. The following aspects are addressed:

- Size of FutureTeeth

- Incisal Embrasures

- Dental Line Angles that Determine Character of Teeth ("Aggressive" versus "Soft" versus "Playful")

- Visibility in Relation to Lip Rise

- Lip Rest Position

- Buccal Corridors

- Color

- Degree of Translucency at Incisal Edges

- Comfort

The cosmetic dentist helps the patient to formulate his/her own goals by explaining the individual design factors. The patient can now make an educated choice, which will be submitted to the dental laboratory. Now the porcelain veneers can be design exactly as the patient desires within the particular functional framework of the oral cavity and the overlying dynamic facial structures.

The new smile is not just objectively beautiful. It also has to be subjectively appraised (by the patient) as a perfect outcome. Only then is the mission accomplished.

Click on images belowe to get to the Smile Galleries:

References:

Magne P, Douglas WH. Rationalization of esthetic restorative dentistry based on bio- mimetics. J Esthet Dent 11(1):5-15, 1999.

Phelan S, Heindl H. Biomimetics and Conservative Porcelain Veneer Techniques Guided by the Diagnostic Wax-Up, Diagnostic Matrix, and Diagnostic Provisional. J Cosmetic Dentistry 22(3): 80-88, 2006.

Yamaguchi K et al. Morphological differences in individuals with lip competence and incompetence based on electromyographic diagnosis. J Oral Rehabilitation 2000(27), 893-901.

Burrow AM. The facial expression musculature in primates and its evolutionary significance. Bio Assays 30(3), 212-225, 2008.

Arnett GW, Gunson, M. Facial Analysis: The Key to Successful Dental Treatment Planning. J Cosmetic Dentistry 21(3), 19-34, 2005.

Naini FB et al. The enigma of facial beauty: Esthetics, proportions, deformity, and controversy. Am J Orthodontic Dentofacial Orthopedic, 130(3), 277-282, 2006.

Davis NC. Smile Design. Dental Clin North Am, 51, 299-318, 2007.

Dong JK et al. The Esthetics of the Smile: A Review of Some Recent Studies. Int J Prosthodontics, 12(1), 9-19, 1999.

Sarver DM, Ackerman MB. Dynamic smile visualization and quantification: Part 1. Evolution of the concept and dynamic records for smile capture. Am J Orthodontics Dentofacial Orthopedics, 124(1), 4-12, 2003.

Ackerman MB, Ackerman JL. Smile Analysis and Design in the Digital Era. J Clinical Orthodontics, 36(4), 221-236, 2002.

Sarver DM, Ackerman MB. Dynamic smile visualization and quantification: Part 2. Smile analysis and treatment strategies. Am J Orthodontics Dentofacial Orthopedics, 124(2), 116-127, 2003.

Sesemann MR. The Diagnostic Tracing Analysis - Visualization by the Numbers. Pract Proced Aesthetic Dentistry, 16(8), 567-572, 2004.

Ackerman JL. A morphometric analysis of the posed smile. Clinical Orthodontic Res, 1(1), 2-11, 1998.

Magne P et al. Anatomic crown width/length ratios of unworn and worn maxillary teeth in white subjects. J Prosthetic Dentistry, 89(5), 453-461, 2003.

Goldstein MB. Long-Term Composite Provisionalization The Staged Rehabilitation. Dentistry Today, 27(12), 80-83, 2008.

Flax H. Creating New Esthetic Veneer Provisionals. Cont Esthetic Restorative Pract, Apr, 2-5, 2004.

Spear FM. The Art of Temporization I. G L Ortho, 1(1), 1-3, 2003.

Spear FM. The Art of Temporization II. G L Ortho, 1(2), 1-3, 2003.

Spear FM. The Art of Temporization III. G L Ortho, 1(3), 1-5, 2003.

Fondriest JF. Using Provisional Restorations to Improve Results in Complex Aesthetic

Restorative Cases. Pract Proced Aesthetic Dentistry, 18(4), 217-223, 2006.

Trinkner TF et al. Achieving Esthetic Goals While Maintaining Proper Bite Relationships Throughout Treatment. Cont Esthetic Restorative Practice, Sept, 38-50, 2003.

Spoor R. Predictable Provisionalization: Achieving Psychological Satisfaction, Form, and Function. AACD Monograph, 1-2, 2010.

Sesemann MR. Diagnostic Full-coverage Provisionals for Accurately Communicating Esthetic and Functional Data. Funct Esthetic Rest Dentistry, 2(20, 8-14, 2008.

Bloom D. Visual Diagnostic Try-Ins: Beyond Dental Imaging. J Cosmetic Dentistry, 23(3), 112-118, 2007.

Michel A. Predictable Smile Design. J Cosmetic Dentistry, 25(2), 110-116, 2009.

Massironi D, Romeo G. Provisionalization as a Communication - Parameter for Definitive Restoration. Pract Proced Aesthet Dent, 14(4), 301-305, 2002.

Predictable Provisionalization: Achieving Psychological Satisfaction, Form, and Function. Pract Proced Aesthetic Dentistry, 16(6), 433-440, 2004.

Mechanic E. Facial Changes Through Dental Temporization. J Cosmetic Dentistry, 24(3), 166-170, 2008.

Gurel G. Permanent Diagnostic Provisional Restorations for Predictable Results When Redesigning the Smile. Pract Proced Aesthetic Dentistry, 18(5), 281-286, 316-7, 2006.

Malone M. Smile design and advanced provisional fabrication. Gen Dentistry, 56(3), 238-242, 2008.

DiTrolla MC. Fabrication Principles for Provisional Restorations in Aesthetic Treatment. AACD Monograph, 1-8, 2010.

Phelan SM, Heindl H. Biomimetics and Conservative Porcelain Veneer Techniques Guided by the Diagnostic Wax-Up, Diagnostic Matrix, and Diagnostic Provisional. J Cosmetic Dentistry, 22(3), 80-88, 2006.

AACD Monograph (no author given). The Temporization Stage: A Blueprint for Successful Aesthetic Restorations. AACD Monograph, 1-2, 2010.

Gray J. Simplified Temporary Techniques for Enhanced Esthetics and Patient Satisfaction. Funct Esthetic Restorative Dentistry, 2(2), 36-40, 2008.

Okuda WH. Aesthetic Transitional Temporization for Success in Cosmetic Dentistry. Pract Proced Aesthetic Dentistry, 18(9), 556-559, 2006.

Bakeman EM. Provisional Restorations for Veneer Preparations. Functional Esthetic Restorative Dentistry, 2(2), 16-22, 2008.

Nixon RL. Provisionalization for Ceramic Laminate Veneer Restorations: A Clinical Update. Pract Periodontics Aesthetic Dentistry, 9(1), 17-27, 1997.

Spear FM. Creating Excellent Anterior Veneer Temporaries: Materials, Techniques and Utilization. AEID, 1-16, 2007.

Cutbirth St. Importance of Lip Type Classification: Maxillary Central Incisor Length Determination Versus Lip Phenotype. Dentistry Today, 2014.

Kim J et al. The influence of lip form on incisal display with lips in repose on the esthetic preferences of dentists and lay people. J Prosthetic Dentistry, 118(3), 413-421, 2017.

Misch CE: Guidelines for maxillary incisal edge position – A pilot study: The key is the canine. J Prosthodontics 17, 130-134, 2008.

Vig RG, Brundo GC: The kinetics of anterior tooth display. J Prosthetic Dentistry 39, 502-504, 1978.

Wazzan A. The visible portion of anterior teeth at rest. J Contemp Dental Pract 15(5), 53-62, 2004.

McGowan S. Characteristics of Teeth: A Review of Size, Shape, Composition, and Appearance of Maxillary Anterior Teeth. Compend Contin Educ Dentistry, 37(3), 164-171, 2016.

Patel JR et al. A comparative evaluation of effect of upper lip length, age and sex on amount of exposure of maxillary anterior teeth. J Contemp Dental Pract 12(1), 24-29, 2011.